- Home

- Amy Conner

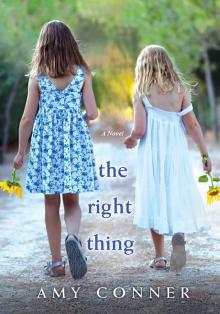

The Right Thing Page 7

The Right Thing Read online

Page 7

Too soon, according to the clock on the stove, Mr. Dukes’s dinner was ready and it was time for me to go home. In the gray light of the fading day, Starr walked with me next door, across the Allens’ sloping lawn, down to the fence dividing their property and our backyard. I tried to climb over the wire, but my legs crumpled like Play-Doh and refused to do their job. No matter how urgently Starr pushed my bottom upward, I couldn’t get to the top of the fence, much less climb over it. Yellow rectangles of light from my house shone through the sunporch windows down across the lawn. I could see the large, white-uniformed figure of Methyl Ivory passing like a ship of state in the center hall between the kitchen and the living room, and falling to my knees, I rolled into a miserable ball on the ground.

Starr knelt next to me in the cold grass. Her face was pinched and nervous in the gathering dark. “Annie,” she said. She shook my shoulder. “Hey. Get up. You can’t lay here. I got to get home—it’s almost time for my poppa to come back.” I couldn’t answer her around the blaze of pain in my throat.

“Wait.” Limber as a cat, Starr scaled the fence, landing with a soft thud on the other side, in my backyard. “I’ll be right back, okay?” The whisper of her bare feet running across the lawn faded into the chill dusk, and the slow rumble of occasional cars over on Gray Street, crickets, the call of a night bird, and the rasp of my own hot breath kept me company instead. The stars came out, one by one. I slept, I think, at last.

Later I woke in my own bed, in my pajamas. In the soft glow of the lamp, my mother and father were sitting on the edge of the mattress. My daddy had his stethoscope around his neck, and my mother’s lovely face wore a worried frown.

“I’m sorry.” That’s what I tried to say, but my throat was a hot hornet’s nest. My mother reached across my father and took my hand in hers. Her fingers were cool, soft, and fragrant with Pond’s hand cream.

“Shh,” she said. “Don’t try to talk, Annie. You’re sick.” Her fingertips touched my cheek. “Poor thing, I remember when I had the mumps. It was awful.”

Daddy smiled down at me. “Now take this paregoric. It’ll help with that sore throat.” Paregoric was nasty stuff, but I was too sick to put up much of a fight. The bitter, banana-flavored thickness slid past my lips, and within minutes, I felt the tidal pull of the liquid’s narcotic undertow. Kissing me good night, my parents turned off the lamp by my bedside, leaving the door cracked open to the bright light in the hall outside.

It was a severe case of the mumps, and all day Sunday I slept, except for one memorable trip to the bathroom where my swollen face in the mirror looked nothing like my grandmother’s. Monday morning Methyl Ivory came huffing upstairs with a glass of ginger ale for breakfast, all I was up to swallowing. I halfway sat up in the bed, feeling like I was going to die of thirst.

“You doing better?” she asked. I nodded as I sipped, my face buried in the tall glass. Cool ginger bubbles popped against my flushed cheeks and inside my nose. “You looking better. Good thing—whole house turn up crazy Saturday night. When Dr. Banks carry you in here, I thought you mama gone fall out, she so overset with you being sick and all.”

“Really?” I croaked. I settled back into my pillows.

“Child,” Methyl Ivory said with a sigh. “I told you daddy and mama how Miz Treeby call and say you run off feeling poorly, and then when you didn’t come home—well, all’s I got to say, Annie Banks, is you mama went just ’bout out a her mind callin’ the po-lice, the neighbors, even callin’ ole Miz Banks. She was fixin’ to go look for you herself when that little gal come knocking at the back door. Look like a scairt rabbit, but she spoke right up, say you run away to her house. She say you was layin’ down sick in the Allens’ backyard and couldn’t get over the fence.” She held out her hand. “Now give me that glass. You get back to sleep.”

That evening, after a day of paregoric-induced drowse and slumber, my mother came upstairs with some cream of tomato soup for me. Placing the steaming teacup on my bedside table, she fluffed my pillows so I could sit up. She shook the glass thermometer, and when I’d put it under my tongue, my mother said, “If your fever’s down, I think you might have some company tomorrow.”

“Company?” I said suspiciously, the word muffled around the thermometer. I was feeling grumpy, although the soup smelled really good.

“Close your mouth and keep that under your tongue. Yes, I was thinking of Starr,” my mother said.

I nearly bit the thermometer in two.

“Not Lisa,” she said. “Not after Saturday. Lollie was horrified when you told her you had pellagra—honestly, Annie, what gets into you?—and I thought Jerome Treeby’s head was going to explode, he was so angry. He acted as though you’d set the house on fire instead of just breaking that ugly old umbrella stand. I guess we’ll have to pay for another one, although where we’ll find one to match it I can’t imagine.”

At the mention of the Treebys, I was suddenly queasy. What else might they have said to my mother? Did she know about the study? My anxiety must have showed in my face, for she stroked my hair.

“Oh, Annie.” My mother sighed. “I don’t know why you didn’t come home, but I don’t want you to run away.” Her eyes were misty. “Never think I don’t love you with all my heart, because I do. A long time ago, I had a friend just like Starr Dukes.” She fished in her skirt pocket for a handkerchief and blew her nose. “Little girls need friends. Even though she’s not the sort of child that I’d choose for you, still . . . I think you could see her every so often.” Taking the thermometer from under my tongue, she read it in the light. “One hundred and some change. That’s good news. Your fever’s down.”

I took a cautious sip of my soup. “What about Grandmother Banks?” I asked. “She says Starr’s trash.”

“Then you’ll play with trash. Besides, Starr said she’d already had the mumps, so you won’t be infecting anybody else. Here. Have some more of this soup.”

CHAPTER 5

“So,” Starr says, “this town being what it is, you must have heard all about me and my situation since before I ran into you.” She switches on one of the ostrich-egg bedside lamps, and in its muted glow the room’s atmosphere softens to a kinder, gentler grisly theme park. “I mean, you came straight here, didn’t even have to ask where I was living.”

“I heard some of it,” I venture, feeling my way here. I don’t want Starr to think I’ve been gossiping about her. I’ll blame it on Dolly.

“Dolly’s mouth flaps at both ends,” I say. “How in the world did you get mixed up with Bobby?” I sink onto the leopard-print chaise. Starr sits on the edge of the monster California king–sized mattress, her legs dangling, looking like a child in an African whorehouse. Her eyes drop to her folded hands, pink nails bitten to the quick.

“It sure felt like the real thing this time.” Her voice is so quiet I strain to hear her. “And I’d been looking for Mr. Right for seeming like forever. Remember Mr. Right? The man my momma told me was going to carry me off, love me forever, and get me whatever my heart desired? Well, Bobby does the best Mr. Right of any man I ever did know.” She glances at me quickly, and if I didn’t know her better, I’d swear her eyes are crystalline with tears. “It was so good in the beginning, Annie. Back then, things were the best—at least till I told him I was expecting a baby.”

I bet. Nothing puts a monkey wrench in the works of a perfectly good thing-on-the-side like a pregnancy.

“Oh, Starr,” I say. “I’m so sorry.”

“Don’t be,” she says. “I’m not.” She mashes the heels of her hands into her eyes, rubbing them. “Not so much.”

“Dolly said you told him you’d rather die than have an abortion,” I say without thinking.

“She said that?” Starr looks at me without expression and is silent for a moment. “Amazing to me how word gets around in Jackson. Well”—she sighs—“that’s one thing I told him. I mean, I couldn’t understand how he would ask me to do that when he’d been swearing up

one side and down the other he was going to leave Julie just as soon as she got back on her feet again, that we’d get married any day now.” Her mouth turns down, bitter with betrayal. “After I told him I was expecting, the truth came out in about five seconds flat. Bobby never meant to marry me at all, he wasn’t ever going to leave her, and wasn’t even going to help me after the baby came. ‘I’ve already got two kids—I’m not going to get held up by some white trash at their expense’ was his exact words.” Starr looks out the window and bites her lip.

My face reddens, remembering the overheard conversation at Maison-Dit. After all, “trailer park” was my first impression before I knew the woman in the hallway was Starr. “He’s a sorry piece of shit,” I say with heartfelt venom.

“Oh, but Annie.” Starr’s eyes have turned dreamy now, her lips curved in a half-smile. “In the beginning, in New Orleans, it was all so . . . special. Early last April, over to the racetrack where I was cocktail waitressing, he came in one night with a bunch of liquored-up lawyers who’d decided to blow all their folding money on the ponies after the convention was over. They were your usual brand of jackass, the kind I’d been dealing with since I was fourteen years old. After I ran away the third time, I got my first job by lying to a motorcycle bar outside of Pigeon Forge, telling the manager I was sixteen, the manager lying to the Board of Health and telling them I was eighteen. When a mess of bikers comes through the door with a load of home-cooked speed on, looking to mellow down with some beer drinking, pool playing, and hitting on the help, you catch on fast.

“But that night at the Fair Grounds, Bobby was different. He told all his drunk friends to leave me alone, to quit playing grab-ass when I served them their margaritas. I remember he was drinking top-shelf whiskey—‘just one ice cube, honey’—and he let it sit in front of him, sipping it slow, just like a gentleman. So good-looking, too, what with his black, black hair and that five o’clock shadow he gets even though he shaves twice a day, the way he wears his clothes like they’re made for him.”

“They are,” I mutter. By some little old man over in Hong Kong. Bobby brags about it all the time. Du’s mentioned more than once that he’d like to get some shirts from the Shapleys’ tailor.

“I know,” Starr says. “Vainest man I ever did meet. Well, Bobby took most of his shit with him after I said I’d throw everything he owned in the bathtub and set it on fire,” she says with a tight smile. “Anyway, after the races were done for the night, his asshole buddies left and I was closing out my shift when he came up and asked real nice, ‘Won’t you have a drink with me? I promise not to break anything.’ His eyes were so sweet, oh—I could of fell into them and melted, just like a dab of butter in hot chocolate sauce. I’d had a long night on my feet, and having a drink with this good-looking man seemed like just the ticket. It was a warm evening for April, and the air like a live thing, wrapping itself ’round my bare shoulders. Bobby didn’t ask me where to go. With the top down on that Corvette of his, we drove to the Fairmont Hotel and drank until close at the Sazerac Bar, talking about this and that, but we both knew we were going to end upstairs in his room on the fifteenth floor.”

“You slept with him the first night you met him?” I don’t mean to sound judgmental, but that’s the way it comes out.

Starr doesn’t seem to mind, for she says, “I did check to see if he was wearing a ring, Annie. He wasn’t. If that makes me a slut, okay, I’m a slut.”

“You are not!” I say fiercely.

“Stupid, then,” Starr says with a sigh. “I should have known better, but like I said, it’d been a long time since the last Mr. Right and he didn’t mention his wife and kids until after we’d already done the deed. The next morning, he ordered up champagne and orange juice from the room service and we stayed in bed for three days straight ’fore we came up for air. He was the best I ever had, and that’s damn good, believe me. Never misunderestimate the power of great sex, honey. It’ll make your best intentions into orphan dogs.”

I’m almost blushing, impressed and more than a little envious. I’ve never known lovemaking like that. Du was my first, and he’s still the only man I’ve ever slept with. For years, I’ve found myself in bed with a man who snores like a grand piano dragged across a terrazzo floor, who hogs the covers and complains about how cold my feet are, so I have no basis for comparison. In fact, in the last few years, we’ve rarely done it at all, and when we do, it’s mainly on the nights when I’m ovulating and hope to make a baby. Then, it’s all up to me to get the ball rolling. After years of temperature taking, charts, and planned sex, Du complains about the lack of spontaneity. He wouldn’t even go in for a sperm count. He swears that all the men in his family have more kids than they know what to do with, so it must be me who’s got the problem.

Starr, on the other hand, sounds as though her romantic past has had all the heat and electricity of a summer lightning storm. “Poppa,” she says, a half-smile on her lips, “always used to say that the wages of sin was death, but I’m still here. I’ve made me some mistakes, but I can’t say I’d do anything different.”

“I wish I could say the same,” I blurt. “Sometimes I wonder what would have happened if . . .”

But I don’t finish the thought because I rarely let myself indulge in what-ifs. They’re like cookies that way. You have one, and before you know it, you’ve had a dozen and regret every last bite. Instead, I look down at my Rolex. It’s four o’clock. The afternoon is suddenly gone, vanished as if I fell down a rabbit hole. I have got to get home before Du does. I need time to get my act together, to get ready to lie to my husband about how I really spent my afternoon, to be dressed and braced for dinner tonight with Starr’s number-one problem—although she doesn’t seem to realize it yet—Judge Otto Shapley.

At this moment, the phone on the bedside table explodes with a series of demanding trills while at the same time another one shrieks from somewhere else in the condo. I expect Starr to reach for the phone, but she says, “I’ll take this up front. Wait here, okay?” Gathering her skirt, she hops off the bed and trots down the hall to the insistent summons of the telephones. I’m left in Bobby country with the stuffed animals, nibbling at a hangnail and dying for a cigarette. I’ve really got to go home.

Five minutes later, knowing I’m really going to be late now, I’m rehearsing my reasons for leaving when Starr walks back in the room. From her compressed lips and distracted expression there’s no question about it. This wasn’t a happy call.

“So,” she says, her eyes cast down on the carpet. “I guess that’s that.”

“That’s what?”

“That was the reason I was trying to get a new dress at Maison-Dit. Before he canceled on me, I sort of had a . . . meeting, an appointment with someone for later on tonight, and needed to be at my best. None of my winter clothes fit me right anymore, and I can’t afford to be looking desperate, not now.” Starr runs her fingers through her curls, pacing. “It was a long shot, anyhow.” She stops and looks over just in time to see me glancing at my watch again.

“Got to go, huh?” Starr asks.

I nod, hoping I don’t look as helpless and guilty as I feel.

“That’s okay,” Starr says. “It’s been good catching up—except we never talked about you, did we?” She leans against the elephant tusk bedpost and folds her arms expectantly. I don’t say anything because I don’t know how to begin, not without a load of self-serving explanations. The room is quiet. You could drop a city bus into the well of deepening silence.

“Guess that talk’s probably not going to happen, is it,” Starr finally says. It’s another one of her nonquestions.

There’s no probably about it. I try to imagine another Ladies’ Leaguer caught up in this mess, like . . . What Would Kendall Do? Kendall Carberry is a walking billboard of the big Southern gal with a big Southern smile, an ace on the tennis court and a crackerjack chairman of the baby-rocking committee. Kendall wouldn’t be caught dead in this situation, the ro

sebush voice whispers. Kendall would’ve disposed of Starr like junk mail the instant she was approached in front of the Walgreens. Kendall would’ve pretended amnesia of her entire childhood if it came down to that or acknowledging a once-friend who’s sunk herself as deep as Starr has. No, Kendall Carberry is no help to me now.

“Oh,” I manage weakly. With damp hands I crush the empty Pepperidge Farm bag into a crumpled paper ball. “I mean, it’s really not like that.”

It is like that.

“I’d love to get together again soon,” I rattle on, “but I need to dash home and get fixed up for this god-awful law partners’ dinner I’ve got to go to tonight.” With a nervous laugh, I get to my feet.

“Law partners?” Starr arches her delicate eyebrows in inquiry. “That’s a surprise. What kind are you?” She waits a long beat for me to answer.

“Oh!” In a head-clap of understanding, I get it. “I’m not the lawyer. My husband, Du. He’s a partner in his law firm.”

Starr nods slowly. “Your husband’s a lawyer? Lord, I surely need to get one of them now. Bobby says I can’t prove this baby’s his and if I say otherwise he’ll sue my ass to kingdom come, drag up every last man I ever slept with and brand me a whore.”

Oh, God, I think. Please don’t let her ask.

“You think your husband would take my case?” she asks, sounding hopeful.

I can’t look at her. Instead, I gaze upward at an immense palm-leaf ceiling fan planted in the middle of an acre of pleated batik fabric, as if the patron saint of cowards is going to open up the penthouse roof and deliver me from this impossible request. When I finally make myself look back at Starr, her eyes are full of questions. Now that same damned silence between us ripples outward in a steep wave, freighted with the weight of those questions. Before I break on the crest of it, Starr saves me.

The Right Thing

The Right Thing