- Home

- Amy Conner

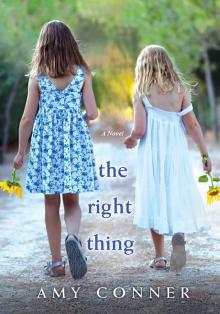

The Right Thing Page 5

The Right Thing Read online

Page 5

“Clues to what?” My mother sounded exasperated.

“Where Starr went! I’m going to be a detective and find her, like Dick Tracy.”

That night my daddy told me in no uncertain terms that I was to cease and desist any and all sleuthing activities. “She’s not coming back, Annie. You’ll have to get used to missing her.” Probably Daddy meant well: certainly he was right about them not coming back, but for me it was as though my seven-year-old world had been broken into shards and would never be whole again.

And truthfully, it seems as though it never really was after that.

I put down my cup, caught up in memory’s net. When you’re in the second grade, you don’t know what the world can do to you yet. That’s the big lie of innocence—that it’s a happy state. In childhood all of the feelings you’ll ever experience in your life come at you with the suddenness and ferocity of mudslides, burying you up to your neck in feelings so overwhelming that you can barely draw a breath from the power of them. My mourning for Starr had been childhood’s first and greatest betrayal. Grown-ups forget that, probably because we’d all go mad if we had to experience what life throws at you every day with the same shock and wailing intensity of just-born emotions.

“Oh, Starr,” I say, remembering that day. “At first, when you didn’t come to school that Monday, I thought you’d for sure be there for the Christmas pageant on Tuesday. You were going to be the Virgin Mary, remember? But when you didn’t show up, that overachiever Lisa Treeby got to have your part instead of being a shepherd because she’d memorized everybody else’s lines. She was such a moose, your costume came up way above her knees and was so tight Lisa had to walk around Bethlehem sideways until it was time for her to sit in the straw and hold the baby. Then those seams ripped right up the sides, almost to her waist. She didn’t dare stand up after that, not even at the end when the Three Kings gave their gifts and everybody clapped.”

“And you were going to be the Angel Gabriel,” Starr says with a half-smile. “Poor ol’ Lisa, having to be head shepherd ’cause she was the tallest in the class. I’m glad she got my part.”

“Julie Posey just about busted a gut, she was so jealous.” Since she’s Bobby Shapley’s wife, I bet she’s miles beyond jealous now. I don’t tell Starr about how Miss Bufkin almost recast me in the play because I kept insisting—loudly—that Lisa couldn’t be Mary, that Starr would be there any minute and we should hold the show.

“But how did you end up here again, in Jackson?” I ask. What I want to ask is, with the wide world to choose from, what possessed you to come back?

“Oh, Annie—that’s a story for another time,” Starr says, waving dismissal. Squaring her shoulders, she gazes out the window at the gray day. “Right now, all I can say is I’m in a heap of trouble.” Her hand goes to her belly protectively.

“Bobby Shapley’s a . . .” I begin, but cannot seem to get the words out. Like a dry worm, dislike catches in my throat. The sacred chains of Annie-be-nice restrain me from saying what I really think of Bobby Shapley, that mean, golden boy two classes ahead of me, Du’s frat brother who cheated his way through college because he couldn’t be bothered to study, the up-and-coming trial lawyer with a wild streak who never lets anything go—not a case, not a grudge, not even a hand of cards—not until he’s done with it. Now he’s done with Starr. Thinking about Bobby Shapley makes me really crave a cigarette because my hand is itching to slap the face right off his head.

“You’re right,” I finally say. “He’s trouble.”

Big trouble. Bobby could get her arrested for any piddly-ass thing he can dream up, make sure she has nowhere to live and no job to put food on the table. Even if Starr tries to take him to court in a paternity suit, she’ll lose: the Judge will see to it. Not a lawyer in town will take her case for fear of Judge Otto Shapley, a retired widower with stone mountains of time and oceans of influence. The Judge won’t let one of his son’s ex-girlfriends drag the family name into the paper, not him, but make no mistake, the old man is a real dog, too. One memorable night at a country club banquet, the Judge followed me outside when I went onto the terrace to have a smoke and made the most startlingly graphic proposition I’ve ever been unlucky enough to receive. Since I couldn’t slap him either, after he was done, I said, “No thanks.”

“You’ll come around,” the old bastard said before he threw his cigar in the boxwoods and went back inside. No, Otto Shapley will crush Starr because she has the audacity to still be here in town, because she hasn’t just given up and gone away.

But both those men are traveling Mormon boys compared to Bobby’s wife, Julie Shapley, née Posey, who in kindergarten was already destined to become the girl with the widest, deepest streak of mean in my sorority pledge class. Freshman year, only once I’d made the mistake of telling her the truth—that her Laura Ashley outfit made her look like an ironing board wrapped in calico—and found myself sitting in the nose-bleed section of the Ole Miss–’Bama game with the geeks from the herpetology department instead of with the other Chi Omegas on the forty-yard line. To this day, when I can, I avoid working with her on the one Ladies’ League committee they let me be on. I shudder to think of what Julie must plan on doing to Starr if she gets a chance.

“And now,” Starr says, “Bobby means to put me out of the condo by the end of the week.” She gives herself a little shake. With an air of bravado, she raises her cup to me, a question in her eyes. “I can make some more.”

“Sure,” I say. I don’t want any more coffee, but it’ll buy me time with Starr and I need this. I can’t believe how badly I need this. “Where’s the ladies’ room?” I ask.

Down a long, white-carpeted hallway I find the powder room, another icebox, albeit one with guest soap and a three-hundred-and-sixty-degree panorama of mirror tiles. They’re even on the ceiling. As I’m washing my hands, I look at my reflections and wonder what I think I’m doing besides trying to commit social suicide, having coffee with Bobby Shapley’s shack-job. Du’s going to kill me if he finds out.

“Shut up,” I say to the reflections, but I’m really talking to the voice in my head, the one that won’t quit about the rosebushes and their secret. Listen, I argue, Starr’s pregnant and even Bobby Shapley couldn’t make her have an abortion. I can be brave enough to have another cup of coffee with her, right? And looking into my own troubled eyes, I’m floored by the melancholy, bone-deep realization that Starr Dukes is truly the first and last best friend I ever had in my life. Hell, the only best friend I’ve ever had in my life. There’ve been other friends, but they weren’t her. Get a grip, Annie, I tell myself and my eyes in the mirrors return the gaze with a dubious resolve.

In the kitchen, Starr’s just finished with the espresso. “Mine’s mostly milk,” she says. “I’ve got to think of the baby.” She pats her belly. “I made you a latte, too.”

“I can’t remember the last time I had coffee that wasn’t black,” I say. The steamed milk is so comforting my taste buds are delirious with the richness of it. This is truly a day for kicking over the traces.

“You’re too thin.” One eyebrow raised, Starr looks me up and down like I’m a starving cat hanging around the back door. “Hold on.” She opens a cupboard and gets a package of Pepperidge Farm cookies down from the shelf. “Have a couple of these.”

My mouth waters at the sight of the white paper bag, but I shake my head. “No thanks,” I say. I’ve got to draw the line at cookies. She shrugs and takes one.

“I love these,” Starr says. “ ’Sides Dr Pepper, they were the only thing I could keep down most mornings, not until about a month ago.”

“When are you due?” The Chessmen cookies are calling my name. I imagine I can smell them from here, buttery sweet with that tantalizing hint of vanilla.

“April sometime. She’s going to be a little Aries.” Starr, finished with one cookie, takes another. “I know she’s a girl,” she says with her mouth full, “ ’cause I had a dream about it. Sure you d

on’t want one?”

I do. Oh, Lord, I do and I’m going to have one and damn the calories. She holds the bag out to me, and I’m careful not to let myself grab it out of her hand. After ages of serial dieting, I’m going to have my first cookie in what I think is about fifteen years.

And I don’t have just one. By the time I’ve finished my latte, I have three. Starr takes another, and we’re at that point of no return with Pepperidge Farm cookies, the part where you’re through one layer and meet the frilled paper cup between the six you just ate and the six waiting for you underneath it.

“Go on ahead, have another one,” Starr says. “You’re company. You want the grand tour?”

Taking the cookies with us, we wander down the pristine hallway, past some more mostly white paintings and statuary, and end up in the bedroom that’s an answer to a decorator’s heartfelt prayer for getting rid of the pieces she can’t move because they’re too obnoxious for a normal house’s sense of what’s right and what’s just wrong. If the living room is a snowed-in spaceport, then the master bedroom is a big-game safari. Under a billowing cumulus of mosquito netting, the mammoth posts on the king-sized bed are faux-ivory elephant tusks, the bedside lamps ostrich eggs sporting stitched ostrich-skin shades. There’s a leopard-print velvet chaise longue, a giant clay urn of peacock feathers, and a fur coverlet on the bed that looks an awful lot like bear. The rest of the furniture is pretty much Zimbabwe rustic with zebra-skin rugs and stuffed animal heads—a gnu, an ibex, a Cape buffalo, and about five trophy bucks—gazing down at us with dusty, glassy-eyed indifference.

“Takes a whole lot of dead animals to make Bobby Shapley feel like a man, I guess.” The words are out of my mouth before I can stop them. It’s the kind of thing I always think but most of the time can keep to myself. Mortified, I turn to Starr, an abject apology ready on my tongue, and I realize she’s laughing.

“Annie Banks, I knew that was you behind that Ladies’ League bullshit!” she says with a delighted smile. “Of course it’s all clear as can be now, but when Bobby talked me into coming back here, I was so in love with his lying self the dead animals didn’t bother me enough to think on them much. Now I tell everyone good night and promise we’ll all get even one day.” She holds out her hand for a cookie. “Laughing makes me hungry,” she says. “It’s good to be hungry.”

I reach into the bag and realize it’s the last Chessman. “Here,” I say, handing it to Starr. She breaks it in two, hands me half.

“Seems like I’ve been hungry forever,” I say around the mouthful of cookie. “It’s nothing to get wound up over.”

“That’s because you grew up on Fairmont Street.” Starr’s tone is matter-of-fact. “When you’re trash, growing up in the back seat of an old DeSoto, hungry means you’re still alive.”

CHAPTER 4

Not Allowed was a terrible thing. It had been over two weeks since I’d talked to Starr, it was a Friday afternoon, and I was skulking past Grandmother Banks’s tall iron-spiked fence by myself with all the stealth of a soldier behind enemy lines. I’d had a trying day at school, and I particularly wanted to avoid my grandmother’s notice. She had the habit of hanging around the front yard in her wheelchair, pretending to supervise Wash, her manservant, waiting for the very moment I would have to pass the front gate. As soon as she caught sight of me and my book bag, she was sure to beckon one palsied, be-ringed finger in an unavoidable summons. This Friday was no different.

“Mercy Anne!”

My grandmother Isabelle Gooch Banks was an imperious creature given to edicts, fiats, and death sentences from the rolling throne of her wheelchair. Served faithfully in all things by her two lifelong servants—Easter Mae, who kept the house and did the cooking, and Wash, who drove the Packard, worked in the yard, and toted my grandmother up the stairs whenever the geriatric elevator went on the fritz—she ruled her empire with a vein-corded fist and a single telephone.

After being released from the day’s enforced idleness, also known as second grade, I had to walk past Grandmother Banks’s State Street house on the way home. The old Banks mansion was something of a local landmark, a moldering three-storied Greek Revival pile complete with formal gardens and a grand porte cochere, garçonnière, servants’ wing, and dank, leak-sprung carp pond. Wash had his work cut out for him, as did Easter Mae, since the house and grounds were designed for Staff, and the Banks family fortunes had dwindled somewhat since the Crash. If my father hadn’t become a pediatrician and had instead followed the family business—doing nothing with style, essentially—my parents would’ve been reduced to living with my grandmother. Our own house, a smaller, much less grand version of the one on State Street, was burden enough. Being a child, I never noticed the constant repairs and economies that afforded my parents their Fairmont address.

“Mercy Anne Banks! Do you hear me?” It was a screech that would’ve shamed a macaw. With a sigh, I swung open the rusted iron gate and trudged up the walk to meet my grandmother, dragging my book bag behind me. Her wheelchair was parked under the shade of an ancient Japanese magnolia, its leaves yellowing and curl-edged after the long, hot summer. The cool spell had dissipated in the last week, just in time for school to start. I was sweating in my red plaid dress, my starched petticoats wilted and white ankle socks bedraggled. My shiny patent leather Mary Janes were covered in dust from the playground.

“I hear tell,” Grandma said with a lifted eyebrow, “that you punched Laddie Buchanan in the stomach yesterday. I know you’re aware that he suffered rheumatic fever when he was an infant and that his heart is weak.” She folded her hands in her lap, eyes sharp in her wrinkled pudding face. “I can’t imagine why you’d do such a terrible thing.”

I scuffed my shoe in the grass, unwilling to look at her. “Laddie’s mean.”

“Mean?” Her voice was deceptively mild. “Why, I’ve known his people all my life. Laddie’s a nice child. Give me an explanation this minute, young lady,” she commanded. Grandmother Banks settled back into her wheelchair for what was bound to be her favorite part of the day: the inquisition. It would be pointless to dissemble in any way because she had a nose for lies. I’d learned that the hard way when I’d tried to blame a broken mandarin figurine on Pumpernickel, her dachshund.

“Laddie’s not nice,” I insisted. “He smells funny, like an old raincoat. Laddie said Starr was trash, right to her face. She’s my friend, and I know it hurt her feelings.” I stuck out my chin. “If that’s not mean, I don’t care what is.”

“It’s truthful, is what it is,” my grandmother said acidly. “That preacher’s child is nothing but trash. Those kind of people move into a neighborhood, and before you know it, nice children are turning up with hookworms and pellagra. Your father says there’s mumps going around on the other side of State Street. Besides, you’ll pick up bad habits. Sassing your elders, eating paste. Your mother”—and here my grandmother sniffed—“did right for a change, forbidding you that little guttersnipe.”

I glared at the ground, stricken silent with the injustice of it all. I didn’t know what pellagra was, much less a guttersnipe, but neither Starr nor I ate paste. Laddie was the paste eater.

“So.” Grandma cocked her head like a malevolent pigeon wearing gold ear bobs. “If you need someone to play with, I’ll speak to Lollie Treeby this very afternoon. You’ll go to their house tomorrow and spend your Saturday with little Lisa.” And with that, I was dismissed.

Wash jerked his white-haired head up from the bed of spider lilies he was tending when I slammed the rusted iron gate on my way out. “Don’t you go shutting the gate like that, Miss Annie,” he reproached me. I kept walking as if I hadn’t heard him, teeth clenched on words unsaid. “That old gate so po’,” Wash advised my retreating back, “I can’t fix it, you go breaking them hinges.”

My grandmother was lightning on the telephone and true to her word. By the time I got home, Methyl Ivory was waiting for me in the kitchen. Wiping her dark, capable hands on a dish towel, sh

e said, “You grammaw called. You going to the Treebys’ tomorrow to play.” From the apparatus assembled on the kitchen table and the bowl of blood-colored batter, it was apparent Methyl Ivory was in the middle of baking a red velvet cake. I dropped my book bag in a despicable heap of homework just inside the back door and flung myself into a kitchen chair.

“I hate her,” I said dismally. The day had seemed like to kill my spirit for good with a whole ream of math pages first thing in the morning; then having to sit next to the acknowledged baron of booger mining, Roger Fleck, at lunch in the cafeteria; plus the agony of no talking to Starr and now a whole Saturday ruined. I propped my chin in my hands, my elbows on the table.

“Who you hate?” Methyl Ivory trolled the eggbeater through the cake batter. “Not that big ol’ Treeby gal—she don’t got three words to say to nobody.”

I stuck my finger in the batter bowl. Methyl Ivory smacked my hand. “No, not Lisa,” I said. “She’s just . . . boring. I hate Grandmother Banks. She said Starr would give me pellagra, that I’d start eating paste and get into trouble. That’s why I have to go to stupid Lisa’s house tomorrow.”

“Mmm-hmm.” Pouring the batter into two greased cake pans, Methyl Ivory gave me a look from under her eyebrows. “Seem to me you don’t need to borrow trouble on you own account. Trouble seem to find you just fine. Here.” She pushed the scraped bowl toward me. “Have that.”

The next morning my mother unceremoniously hauled me out of bed.

“Wake up, Annie Banks.” She jerked the curtains open to a gray morning. “I’m walking you down to the Treebys’ in half an hour.” My mother tossed some clothes onto the bed. “Put these on.”

I yawned and scratched, eyes at half-mast and hair frowsy, looking with distaste at the inoffensive yellow shorts and blouse. I took as long as I dared getting dressed. Later, in the bathroom, the black and white tiles were cool under my bare feet, the old-fashioned toilet dripping while I stared at my reflection in the wavy mirror over the pedestal sink. As I brushed my teeth, it came to me with a dawning horror that my eyes were the very same color as my awful grandmother’s—the deep blue of autumn thunderclouds—and though hers were silver and mine were blond, I had her eyebrows, too. In a fascinated kind of dread, I was examining my nose, my chin, my toothpaste-whitened mouth for further resemblance when my mother burst into the bathroom.

The Right Thing

The Right Thing